I’ve been wondering recently whether buildings have the ability to retain some of the emotion and human spirit of the occasions and experiences that have unfolded within them over time.

This question has asserted itself more since I became the lucky custodian of St. Clement’s Church in Eurobin, a now lovingly restored rural Gothic church, built quickly in 1910.

What is it, really, that makes a place sacred?

What Makes a Place Sacred? St. Clement’s Church Eurobin and the Memory in Its Walls

At first glance, one might be forgiven for thinking the answer lies in religion – or more precisely, in religious rites. These, of course, are commonly held at churches, temples, and other blessed spaces. But I’ve come to believe that sacredness is something deeper and more expansive.

Some of the structured rituals of Wiccans, for example, or the more eclectic traditions embraced by other witches, involve casting a sacred circle to create a space for ritual and divine connection. This might take place anywhere in nature, and once the rite is complete, there’s often no physical trace left behind – yet the moment was sacred all the same.

Sometimes, after a loved one has passed, family or friends will install a bench in their memory – a seat with a small plaque, perhaps tucked beneath a favourite tree or overlooking a much-loved view. These become places of quiet reflection, where people go to sit, remember, and reconnect. Though humble, these spaces could absolutely be considered sacred – not because of religion, but because of presence, memory, and love.

And so, the fact that St. Clement’s was deconsecrated in 1971 doesn’t, in my view, diminish its sacredness. Far from it. I believe it is still alive with the fabric of its memories – a quiet witness to more than a century’s worth of vows, prayers, tears, laughter, and song.

I realised how the emotional tone absorbed by the walls of St. Clement’s Church must have shifted in response to all the events a century brings. It’s only a small church, but the moments people have lived through together – gathering to reflect, to cry, to celebrate, and to feel the warmth of community – have been monumental.

A Church Is Born: Building St. Clement’s in Early 1900s Eurobin

Back when the Eurobin community, chiefly led by the remarkable Mrs Agnes Walkear, was rallying to raise funds to build St. Clement’s, the area was a rural patchwork of farmers, orchardists, and small landholders. This fertile region, with its cold winters and long, dry summers, was – and still is – ideal for growing apples, pears, stone fruits, chestnuts, and walnuts. Produce was sold at local markets or loaded onto trains bound for Melbourne.

It’s fair to say that Eurobin’s population was tied deeply to the rhythms of the land and the seasons. Orchards flourished. Dairy farms supplied the valley and nearby towns. In a global sense, there were murmurs of unrest in Europe, but they were distant topics – reported sparsely in newspapers and often without much context. There may have been a general awareness that all was not well on the other side of the world, but the outbreak of war in August 1914 would still have come as a huge shock for many in the area.

Hope and Heartbreak: World War I and the Spanish Flu in the Ovens Valley

A surge of patriotic feeling followed. Australia was still a very young nation – only 13 years into Federation – and ties to the British Empire remained strong, even in small localities like Eurobin. The newspapers of the day are littered with articles about fundraising efforts for the various patriotic causes. Locals began enlisting and sending supplies. Families watched as their sons boarded trains headed for military training…

In 1914, St. Clement’s was still a relatively new addition to the landscape. The timber was fresh. The iron roof was just getting used to the seasonal rhythms of rain and sunshine. But inside, the emotional fabric of the church had begun to be woven with darker threads – absorbing the weight of fear and hope in equal measure.

The once cheerful gatherings and christenings of this close-knit farming community gave way to sombre prayers, whispered worries, and the sharing of newspaper clippings from distant places many couldn’t even picture. Young men who had once slouched in the pews, half-listening to sermons, were now being farewelled at the altar rail with tears and blessings from those who loved them. Mothers clutched prayer books more tightly.

The minister spoke more often of duty and sacrifice. Slowly, the air inside the church grew heavier – filled with the growing awareness that life, even in quiet Eurobin, would never quite be the same again. Losses were felt deeply. The names of young men who never returned would have been mourned in hushed Sunday services. The church became a place to make sense of absence, grief, and pride.

(Image via Wikimedia Commons)

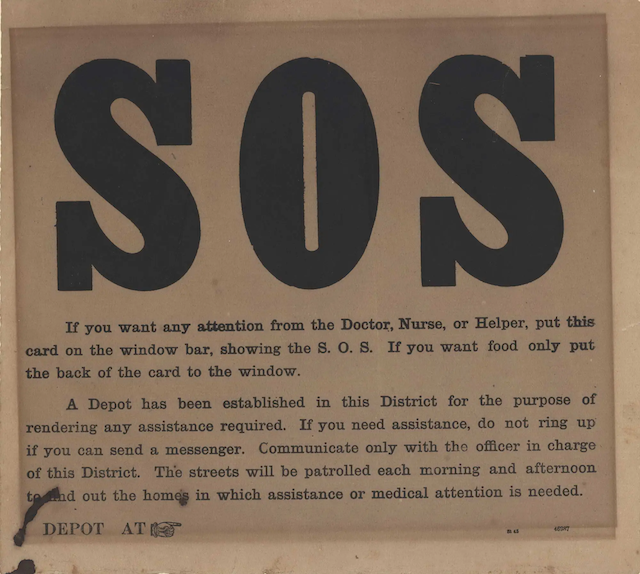

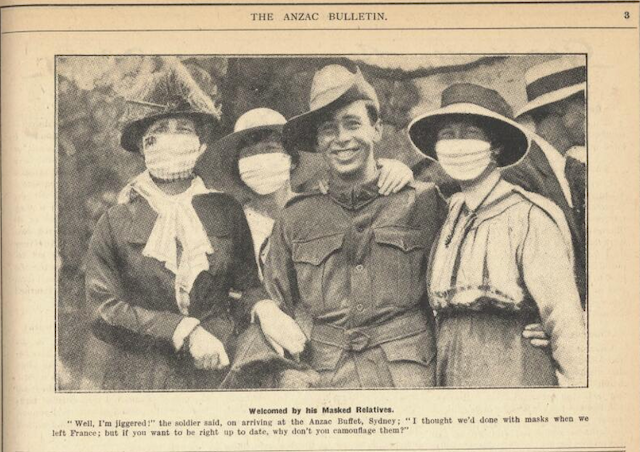

Just as the community may have begun to feel a return to normal after the Armistice in 1918, the Spanish flu shattered that hope. Infecting up to two million Australians and claiming almost 15,000 lives – many of them young adults – the virus ravaged a country already exhausted by the Great War.

In rural Victoria, localities such as Eurobin would have experienced their relative isolation as both a blessing and a curse. Distance from major population centres may have delayed the flu’s arrival, but once it reached these small communities, limited medical infrastructure made treatment and containment incredibly difficult.

(Image from www.joseflebovicgallery.com)

Rail connections, like the one then running through Eurobin, were vital for trade and travel – but also for spreading infection. Stations in nearby Myrtleford and Bright would likely have been key entry points. Public gatherings were restricted. Churches like St. Clement’s, which had once held prayers for safe returns, now likely hosted hurried funerals or quiet vigils for those lost to illness rather than war.

(Image from: forgottenaustralia.com – Episode 1 – “Sister Annie, Sydney and The Spanish Flu”)

It’s likely the church closed its doors for a time, or opened only to limited, spaced-out congregations, meeting quietly under the weight of this new grief. Once again, the timber walls of St. Clement’s absorbed a collective sorrow – not the patriotic anxiety of young men going off to fight, but the quiet anguish of families losing loved ones close to home, to something they couldn’t even see. The fresh relief of peace was replaced by mourning all over again, and the emotional fabric of the place grew more layered, more complex – stitched now with silence, illness, and the ache of unfinished celebrations.

The 1920s in Eurobin: Recovery, Renewal, and Rural Life

As the 1920s unfolded, the Eurobin community, like much of the country, began the slow process of rebuilding. Grief still lingered in the air like a season reluctant to pass, but there was also renewal.

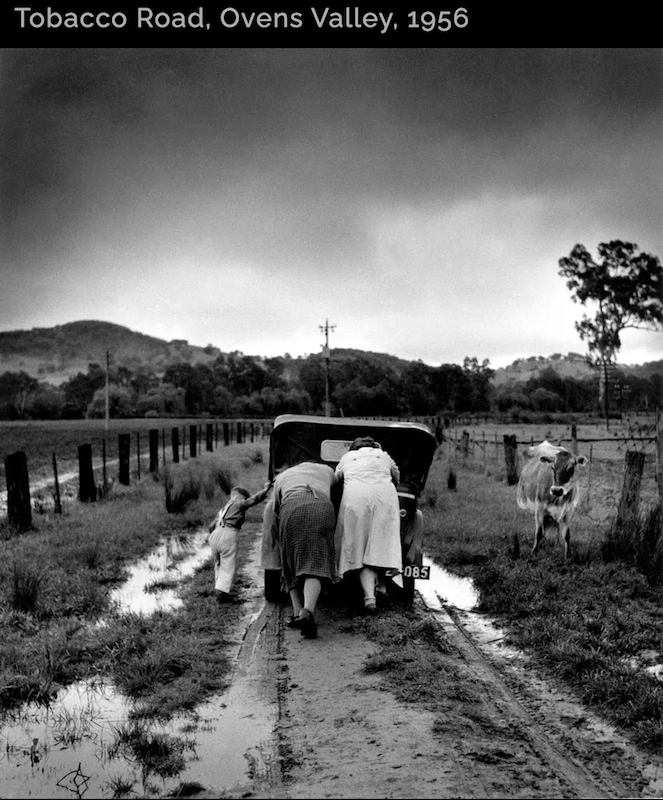

Tobacco farming began to take root in the region’s economy. The valleys and hillsides around Eurobin were soon dotted with neat rows of tobacco plants, and the distinctive curing kilns – small brick or tin sheds with chimney stacks – became a familiar sight. Tobacco was labour-intensive, and the industry drew workers from across Australia and eventually many post-war European migrants, especially Italians, who brought with them a strong work ethic and rich food and farming traditions that would help shape the character of the region.

(Image via Trove trove.nla.gov.au)

Harvests resumed. Fruit trees blossomed. Babies were born to families who had waited long for joy. Some young men returned from war with sweethearts, and new unions were blessed beneath the humble rafters of St. Clement’s. White ribbons fluttered on the church fence once more. Flowers, not just wreaths, but bridal bouquets, returned to the altar.

Nestled along what locals once called Tobacco Road – now the Great Alpine Road, St. Clement’s quietly witnessed decades of change, its weatherboard walls absorbing the rhythm of rural life as tobacco fields thrived around it.

(Photo via Jeff Carter Archive)

The sorrow etched into the church’s walls remained, but so too did a quiet strength. Services may have taken on a more reflective tone – fewer booming sermons, more gentle prayers for healing, gratitude, and peace. Laughter, once held back, began to bubble up again at shared suppers and community picnics.

The Women Who Held the Valley: CWA, St. Clement’s, and Rural Strength

In the decades following Federation, Australia stood as a pioneer in women’s rights – becoming one of the first nations in the world to grant women the right to vote and stand for federal parliament in 1902. But it was in the quieter, determined steps taken in rural communities like the Ovens Valley that this progress truly began to reshape everyday life. By the late 1920s and early 1930s, the newly formed Victorian branches of the Country Women’s Association (CWA) were beginning to blossom.

Local women – orchardists’ wives, dairy farmers, mothers, and homemakers – gathered in halls, homes, and sometimes even churches like St. Clement’s, sharing knowledge, raising funds for health services, and supporting one another through the practical challenges of remote living. These gatherings quietly transformed spaces like St. Clement’s from places of worship into places of connection, empowerment, and growing confidence – where the spirit of community was strengthened not just by faith, but by the hands and voices of women working side by side.

Tobacco Fields and Radio Waves: Life Along Eurobin’s Tobacco Road

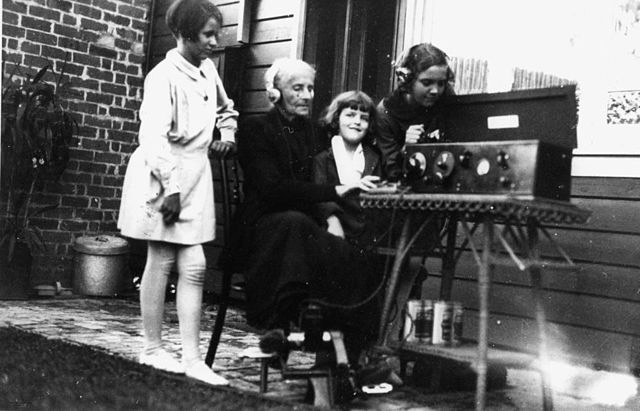

A new sound arrived, too – the warm crackle of a wireless radio. In the 1930s, more homes in the region began tuning in to news, music, and stories from afar. Families might gather in the evenings, voices hushed as they listened to cricket scores, King George’s addresses, or serial dramas that made even the most isolated farmhouses feel less alone. Radio brought a new kind of companionship – invisible yet deeply felt.

(Image via Wikimedia Commons)

St. Clement’s stood quietly through it all – a witness not just to loss, but to resilience, love, and the continuation of life. It wasn’t just funerals and whispered prayers for the absent anymore. It was christenings. It was weddings. It was neighbours sharing apple cake (made, no doubt, from Eurobin apples!) on folding chairs in the sun after church. Inside St. Clement’s, time seemed to slow just enough for people to catch their breath – and, perhaps, to believe again in the goodness of life.

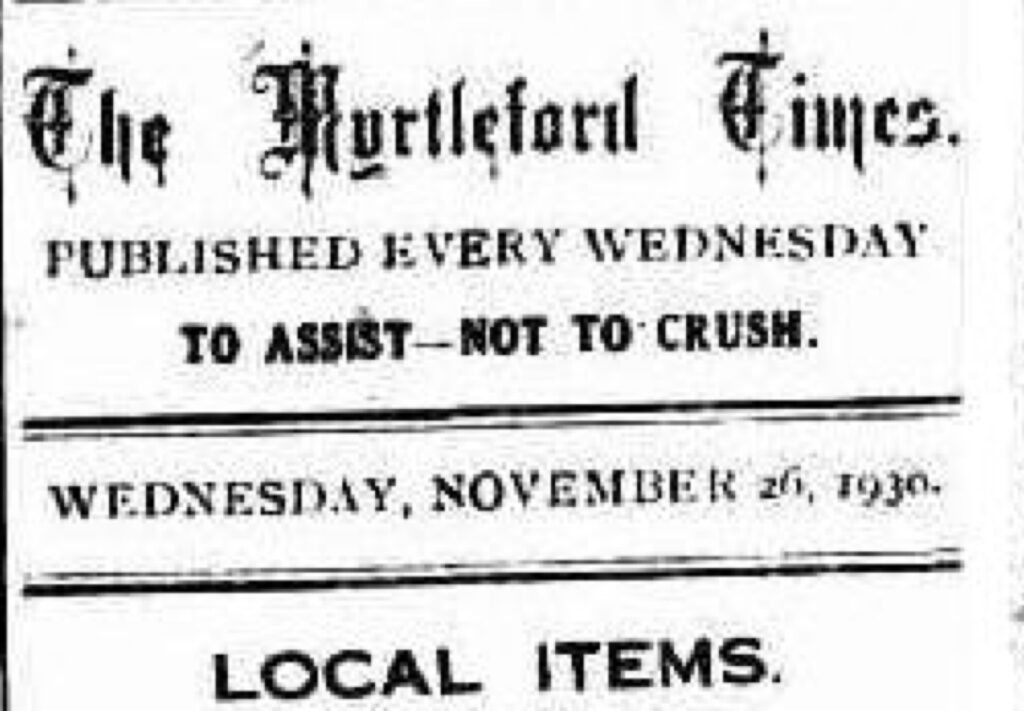

The Great Depression in Eurobin: Scarcity and Spirit

As the 1930s unfolded, the weight of the Great Depression settled heavily over rural communities like Eurobin. The Depression – a global economic collapse triggered by the 1929 stock market crash – caused prices for goods to plummet and work to dry up. In the Ovens Valley, fruit prices collapsed, farm incomes dwindled, and some families lost the land they’d worked for generations. At St. Clement’s, sermons turned toward themes of endurance and compassion. Prayers for rain and stability grew more urgent, and the church became a place not only of worship, but of quiet charity – where neighbours gathered not just in faith, but in mutual need.

(Image courtesy of the Myrtleford & District Historical Society)

The train still rattled through Eurobin, carrying produce to market and news from the wider world. Cars began to appear on country roads. While some locals left for brighter lights, others stayed – firmly planted, akin to the walnut and chestnut trees that abounded.

World War II in Eurobin: Resilience, Weddings, and St. Clement’s Church

The 1940s arrived not with fanfare but with a heaviness that settled into the bones of the country. Though the scars of the Great War had not yet fully healed, another conflict began to stir across the seas – louder, more widespread, and with shadows that reached even further than the first. The world was at war again, and once more, the rhythms of rural life in Eurobin were disrupted by something vast and far beyond its peaceful hills.

At St. Clement’s, the walls – already familiar with the ache of farewells and murmured prayers – braced quietly for another storm. The timber may have aged, but the church’s heart remained strong, ready once more to hold the grief, the worry, the waiting.

Young men, some of whom had been christened beneath the vaulted wooden ceiling or had fidgeted through Sunday services, now stood at the altar in uniform to exchange hurried vows before boarding trains south. The church was never still for long. Its space was filled with quiet resilience: women gathering to knit socks and roll bandages, children learning the silence of sacrifice, and neighbours sharing what little they had with one another.

Though far from the front lines, Eurobin was not untouched. News from Europe came slowly but hit hard. Ration books replaced shopping lists, and once-bright community events became subdued affairs. Even in the Ovens Valley, there were fears of invasion; blackout cloths were kept ready, and anxious glances met the crackle of a radio bulletin.

Inside the church, the sermons may have quietened, but the prayers became more urgent. Words like protection, strength, and safe return were spoken often – murmured in pews, whispered at the altar. Over time, the timber walls absorbed every heartfelt plea, offering no judgment for the tears that fell quietly beneath their watch.

Even during wartime, joy found a way in. Couples stood at the simple altar of St. Clement’s, exchanging vows in borrowed clothes, with wildflowers gathered from the roadside and nervous smiles shared between family and friends. There were no bells and no lavish receptions – just heartfelt promises and the quiet beauty of a community bearing witness. When the old organ sounded its few familiar notes, it wasn’t grandeur that filled the air, but something softer and stronger: a thread of hope, stitched into the very timbers of the church.

From Harvests to Silence: The 1950s, 60s and the Long Pause

In the decades after World War II, rural rhythms returned, but life in the Ovens Valley had shifted. The 1950s and 60s brought a mix of steady labour and slow decline. Hop farming was at its peak in Eurobin, drawing seasonal workers from near and far. Each autumn, the valley came alive with the scent of drying hops and the rustle of vines climbing tall wooden trellises. It was hard work – repetitive, physical, sun-drenched – but for many, it meant food on the table and a pocketful of wages in hard times.

(Image via Trove)

(Image via Trove)

(Photo by Jeff Carter, via Facebook)

But while the paddocks buzzed with activity, the little church grew quieter.

St. Clement’s congregation began to dwindle. Families moved, aged, or simply stopped attending. The social fabric of rural life was changing. The last official service was held on Mothering Sunday in 1971, witnessed by just four people. The minister’s handwriting in the parish record book marks the moment with quiet finality. There was no grand farewell – just the slow fading of voices that had once filled the space.

After that, the building entered its long silence.

The decades that followed were not kind. The church sat unattended for many years. In several surviving photographs from this time, trees and scrub creep up around the entrance, softening its edges not with garden flowers, but with neglect. Forgotten is not too strong a word.

(Photographer unknown)

And yet, despite the years of disuse, the church endured.

In the late 1980s, a quiet shift occurred. Rupert and Josie Saines, the owners at the time, began allowing couples to marry at St. Clement’s once more. There was no brochure, no formal signage – just word of mouth and a willingness to share something beautiful. Brides and grooms stood on bare boards, surrounded by old weathered walls and handmade pews. There was no altar cloth, no priest unless one was brought, but there was a kind of grace in that simplicity.

The church was no longer consecrated, but it had never stopped being sacred.

It’s difficult to explain to someone who hasn’t felt it – that quiet, almost imperceptible shift in the air when you step inside an old building like St. Clement’s. There’s no plaque that lists its emotions, no obvious sign of its scars or joys, and yet… you feel them. Over more than a century, the wooden frame has absorbed weddings and funerals, quiet blessings and unspoken doubts, childhood laughter and wartime tears. These moments linger like threads in a vast, invisible tapestry, stitched deep into the timber and floorboards.

Unlike a brand-new building – still clean, still waiting – St. Clement’s is already full. Full of memory. Full of feeling. And perhaps that’s what makes a place sacred, after all. Not the rituals performed, or the doctrines preached, but the way a space holds the weight of human life – quietly, humbly, without demanding to be seen. St. Clement’s is small, yes. Simple. But it has endured. And in doing so, it has become more than a building. It is the last one standing, and still, it holds the fabric of a whole community’s spirit.

Comments +